In examining the next chapter of Tanner Street’s history, we must first consider the life of Richard Russell.

Richard Russell

In the late 18th century, Five Foot Lane was renamed Russell Street after Richard Russell, who was a Justice of the Peace for the county of Surrey. Russell was certainly a larger-than-life character. A Woolstapler by trade, he collected art and was a member of the Royal Society.

Russell evidently played a full part in the Parish of St. Mary Magdalen during his lifetime. His 1784 obituary in The Gentleman Magazine reported that;

As an inhabitant of a large parish, and as a commissioner of the pavements and sewers, he was always opposed to improper expenditure of public money, and was ever ready to pay any sum on such occasions out of his own pocket, rather than put the parish, or commission, to the least charge.

Richard Russell had inherited a sum of around £10,000, a fortune by modern standards, left first to his mother by his father John, who had built up a successful business as a Fellmonger. He often put his fortune to good use, rewarding his servants with handsome salaries and supporting the parish charity school. You can find his name recorded on the stairway in the northwest corner of St Mary Magdalen on Bermondsey Street. His interest in the arts extended to sculpture, and he left a large sum of money for a monument to himself in St John’s, Horselydown, where he elected to be buried as St Mary Magdalen did not have the room for a memorial of such a large size.

It seems, however, that he was not universally loved, as the Gentlemen Magazine explains;

He had a kind of a cynical turn, which led him frequently to oppose the sentiments of others; and that rendered him in a degree unpopular. Those who knew him best were not disgusted with his character, which, though odd, blunt, and singular, was sometimes thought entertaining and always honest.

A short account of the Parish of Bermondsey, published in 1868, recounts the story of Russell’s extraordinary funeral;

After willing various large sums of money to different charities, he desired that £500 be spent on his funeral, exclusive of £50 each to six young women who were to be pallbearers, and £20 each to four other young women who were to strew flowers before the corpse. He was buried at St. John’s, Horsleydown, a sermon being preached by the rector, Mr. Penneck, which Mr. Russell expressly desired might be a short one, and which the tumult prevented being heard.

Less than charitable Church Commissioners

In 1740 church commissioners bought out the remaining 10 years of an existing lease for land and buildings used to benefit the poor and originally owned by Owen Clunn in the 16th century. In 1746, the parish ordered that a workhouse be built for 250 people on the same site.

This change of usage clearly caused dissatisfaction as a report by Parliamentary Commissioners reveals;

It appears to us that as these premises were given for specific charitable uses, clearly defined by the donor, the parish are not justified in appropriating them to another purpose.

Owen Clunn had indeed willed his land for “the use of the poor of the parish of Bermondsey for ever” [see the previous article]. The Charity Commissioners report, however, was somewhat late, being issued on 4 December 1826, some 80 years after the earliest Workhouse had been built. They did, however, recommend that the parish should remain accountable to Clunn’s wishes;

We think that the parish should pay a reasonable rent for the work-house, which is estimated at about 20/. a year, of which 21.12s should be added to the weekly gift of bread and the remainder should be applied in a distribution of coals as directed by the donor.

The Workhouse was extended over the years, and its presence certainly dominated Russell Street. The census of 1881 tells us that William White Parkinson was Workhouse Master at this time, helped by a staff of 16, of which 7 were nurses. There were 267 residents, of which 115 were labourers, 8 Tanners, and 5 Leather dressers. Occupations of other residents included Farrier, Twine Spinner, Seaman, Sailor, Mariner, Shoemaker, Currier, Blacksmith, Joiner, Shipwright, Painter, Skinner, Deal Porter, Barge Builder, Lighterman, Paper Maker, Slater, Hop Sampler, Wire Weaver, Commercial Traveller, Cooper, Cordwainer, Rigger, Sawyer, Pork Butcher, Hawker, Draper, Printer, Clerk, Mason, Scavenger, Coal Porter, Shepherd, Rope Maker, Brick Layer, Furnaceman, Carpenter, Engine Fitter, Warehouseman, Cook, Tailor, Chimney Sweep, Green Grocer, Hoop Bender, Sadler, Compositor, Last Maker, Leather Presser.

Bermondsey Workhouse, 1825 by John Buckler

Victorian workhouses were austere, to say the least. A ‘hostel of last resort’ for parishioners who may have fallen on hard times, suffered through illness and had nowhere else to live. Much of Bermondsey was low-lying and then without embankments to protect the area from flooding. The Lancet (4 Nov 1865), in a report on the conditions at the Russell Street workhouse, noted;

The whole site is below high-water mark, and formerly was part of the bed of the Thames. The consequence of this is that the house is often flooded, the water standing two feet deep in the basement!

Of course, these same tidal streams of the Thames made Bermondsey a perfect location for tanneries, which used the waters to cleanse skins in the tanning process.

Many who found themselves at the Workhouse lived transient lives. Working conditions and certainly workers’ rights were often non-existent, and many were trapped in a zero-hours culture of employment, which often left them unable to find permanent lodgings.

The Lancet (4 Nov 1865) explains;

The peculiar conditions of the parish render it inevitable that this class of paupers should exist in great numbers, the fluctuations of commercial and manufacturing operations frequently throwing many working people at once out of employment; and as these poor folk are not distinguished by provident habits, their application for casual relief follows as a necessary consequence.

Russell Street, Bermondsey 1832

Bermondsey and The Land of Leather

By the end of the 18th century, Russell Street had joined up with Bermondsey Street, and the map from 1832 indicates that there was still a considerable area of open ground to the south. A large area to the north of Russell Street was laid out as a Tenter Ground and used for drying newly manufactured cloth after fulling where the wet cloth was hooked onto frames called tenters and stretched taut so that the cloth would dry flat and square.

Russell Street, Bermondsey, 1874

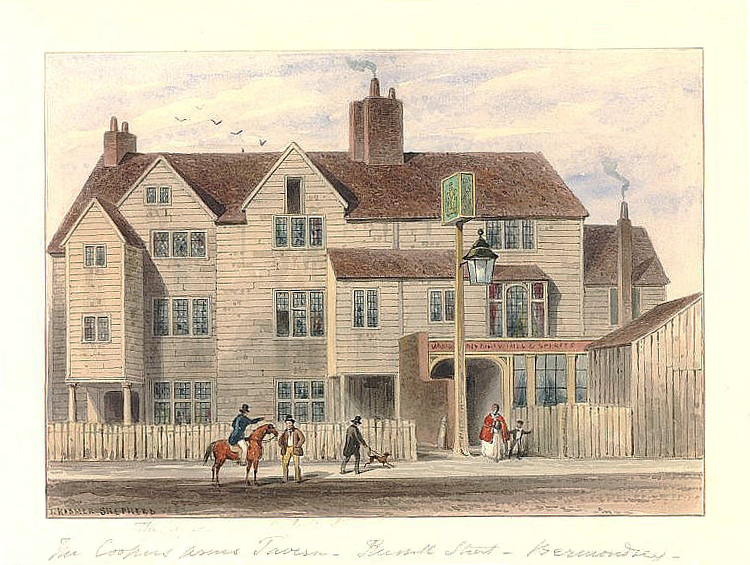

A later OS Map of 1874 shows wool and hop warehouses, tanneries, and currieries marked everywhere. It was estimated that by the end of the 18th century, a third of all leather was manufactured in Bermondsey. Many leather dressers were drawn to the area, and Bermondsey was known as “The Land of Leather”. The Vinegar works (later known as Sarson’s) can be seen for the first time, and the expanded railway from Greenwich, Croydon, etc., makes its way into London Bridge Station. This map also provides evidence of housing on Russell Street, and east of the Workhouse lies George’s Place totalling 54 dwellings crammed into a tiny area. Bermondsey was not short of pubs, inns, and taverns, and the Cooper’s Arms Tavern was located on the site of modern-day Tanner House. Rowlands Court and Finimore’s Court, located next door, accounted for a further 16 dwellings and backed onto Brunswick Court. Other public houses included the Blue Anchor at 61 Russell Street, the Raven and Sun at 27 Russell Street, and the Stingo Arms at 86 Russell Street.

It is easy to forget that Tower Bridge Road was not yet built, and the route of Russell Street continued unbroken to Dockhead. Much of this section of the road has also been developed for tanning and leather making. By the end of the 19th Century, the area will have been thick with the smells of industry and Bermondsey was ready to rebrand the roads in and around Bermondsey Street with new names. Russell Street was soon to become Tanner Street.

Sources

workhouses.org.uk by expert historian Peter Higginbottom

Richard Russell, The Gentleman’s Magazine, Vol 54

A Short Account of the Parish of Bermondsey

Further reading

Tanner Street, Bermondsey